Early onset intrauterine growth restriction

Abstract

Intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR) is a complex multifactorial pathology that has both perinatal and obstetrical implications. Early onset IUGR leads to more severe complications.

Prenatal ultrasonography is the gold standard in screening, diagnostics, and management of cases with IUGR.

We chose to present from the experience of our clinic a severe case of early-onset preeclampsia and major IUGR.

A 35 years old primipara with Panorama screening test for chromosomal anomalies and preeclampsia risk screening based on biochemical (PAPP-A), biophysical and medical history, both classified at low risk; by the 20th week of amenorrhea, there was an important difference between foetal development and chronological gestational age.

Starting with the 23rd week of gestation, proteinuria values began to change, in 10 days presenting signs of nephrotic syndrome (22g/24h proteinuria, 2.8g hypoalbuminemia, hyperlipidaemia). At 26 weeks of gestation, the status of the foetus began to deteriorate severely: absent amniotic fluid, absence of gastric stomach, hypoplastic lung areas, absence of diastolic flow in umbilical artery.

The severe evolution of IUGR was associated with the death of the foetus at 27 weeks of pregnancy and vaginal delivery. Its weight was 490g (under 1st percentile) and the placenta weighted 100g (below the 3rd percentile).

The case’s particularity is represented by the early on-set of preeclampsia, although the screening results showed a low risk that was complicated with major and rapid progressive IUGR.

Table of Contents:

1. Introduction

2. Discussions

3. Conclusion

1. Introduction

Intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR) affects 5-10% of all pregnancies, and it is the second cause of perinatal morbidity and mortality [1].

IUGR is a complex multifactorial disorder that has both obstetric and perinatal implications [2], [3]. The best method for screening, diagnosis, monitoring and management of IUGR is ultrasonography. Many authors and medical schools tried to define IUGR using biometric parameters (weight percentile), Doppler (umbilical artery, middle cerebral artery, uterine artery, and ductus venosus), and biochemical markers. Gordjin and co published in Ultrasound in Obstetrics and Gynaecology in 2016 the definition of IUGR based on Delphi procedure. Early on- set IUGR has an arbitrary cut off at 32 weeks of gestational age (GA) and has three defining parameters: (i) foetal abdominal circumference below the third percentile for GA/ estimated foetal weight below the third percentile for GA/zero diastole of the umbilical artery in Doppler (isolated criteria) and (ii) estimated foetal weight or waist circumference below the tenth percentile for GA and the pulsatility index of the uterine and umbilical arteries above the 95th percentile for GA (combined parameters) [4].

The use of uterine artery Doppler as a parameter associated with birth weight below the tenth percentile for diagnosing early FGR have been criticised because uterine artery Doppler showed low sensitivity in a meta-analysis on the prediction of adverse perinatal events in FGR [5] .The choice of 32 weeks as the cut-off value appears appropriate because hypertrophy of foetal cells initiates approximately at this GA and it is the most commonly used age in the main study on IUGR [5].

Case report

A 35 years old primipara with Panorama screening test for chromosomal anomalies and preeclampsia risk screening based on biochemical (PAPP-A), biophysical and medical history, both classified at low risk.

At 17 weeks of gestation, the patient developed signs of cervical incompetence and a cervical cerclage was performed. At this age we already notice a difference of five days between the chronological age and AUA GA.

By the 20th week of amenorrhea, there was an important difference between fetal development and chronological gestational age, both estimated fetal weight (EFW) and abdominal circumference (CA) being placed under the 1st percentile (Table 1), the amniotic fluid index (AFI) was 7 and the Doppler exam in umbilical artery (UA) showed inconstant the absence of end- diastolic flow. The blood pressure began to rise progressively from 140/80 mmHg to a maximum of 190/120 mmHg within three weeks.

Starting with the 23rd week of gestation, another complication was noticed: proteinuria values began to change, in 10 days presenting the signs of nephrotic syndrome (22g/24h proteinuria, 2.8g hypoalbuminemia, hyperlipidaemia). Further investigations and consults revealed no renal or cardiovascular cause.

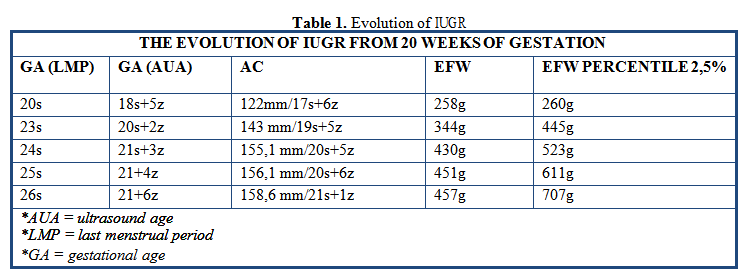

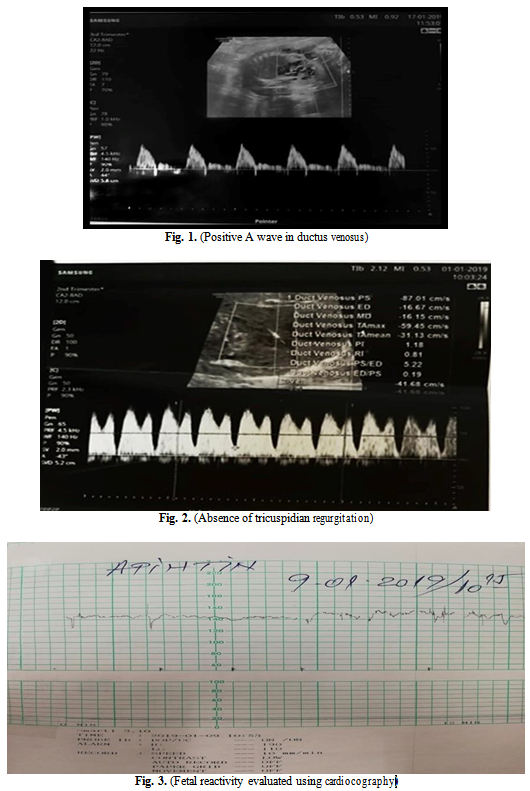

In the assessment of a proper time to terminate the pregnancy we tracked the following three parameters: positive A wave in the ductus venosus (Fig. 1), the absence of tricuspidian regurgitation (Fig. 2) and fetal reactivity evaluated using cardiocography (Fig. 3).

At 26 weeks of amenorrhea, the status of the fetus began to deteriorate severely: absent amniotic fluid, absence of fetal stomach, hypoplastic lung areas, absence of diastolic flow in umbilical artery.

The patient began to develop ascites based on hypoproteinaemia (fluid spaces are visualized in the abdomen, including the hepato-renal space).

The severe evolution of IUGR was associated with the death of the fetus at 27 weeks of pregnancy and vaginal delivery. Its weight was 490g (under 1st percentile) and the placenta weighted 100g (below the 3rd percentile). The patient’s evolution after delivery was favourable, blood pressure two days after fetal expulsion kept around 120/80mmHg.

2. Discussions

Preterm birth, low birth weight (LBW), and IUGR are worldwide the leading causes of neonatal, infant, and childhood morbidity, mortality [6].

In observing this particular case, we can see the evolution of the EFW from 20 weeks of gestation was below 1% percentile and as studies suggest, the perinatal outcome of IUGR is dependent on the severity of growth restriction; an estimated fetal weight below the 3rd percentile and/or abnormal umbilical artery Doppler are strongly associated with adverse perinatal outcome. [7]

Early IUGR is strongly associated with hypertensive disorders of the pregnancy and preeclampsia. [8] Studies show that the syndrome of preeclampsia leads to a failure in physiologic increase of uterine perfusion during pregnancy because of poor placental implantation and development. [9]

Early on detection through screening could help with managing both conditions and has been the key subject of the last 10 years of studies. [10]

The preeclampsia risk screening based on a combination of uterine artery Doppler with first- trimester maternal serum markers, risk factors and medical history failed to detect it in this case, although first-trimester uterine artery Doppler can identify over half of women who will develop preeclampsia. [11]

In general, the screening performance for preeclampsia and early on-set IUGR is considered superior than for late on-set disease.

The use of combined screening which includes placental biomarker PIGF-placenta growth factor can detect 100% of cases with preeclampsia in pregnancies under 32 weeks. [12]

Therefore, the use of a combined screening which includes PIGF in the first trimester of pregnancy, could help obstetricians in initiating early treatment with aspirin. [13], [14]

3. Conclusion

The case’s particularity is represented by the early on-set of preeclampsia, although the screening results showed a low risk that was complicated with major and rapid progressive IUGR.

The Authors:

CONSTANTINESCU Camelia [1] [2]

BOBEI Tina [1]

CALO Ioana Gabriela [1]

[1] “St. John” Hospital, “Bucur”, Maternity, Bucharest, (ROMANIA).

[2] UMF “Carol Davila”, Bucharest, (ROMANIA).

Contributo selezionato da Filodiritto tra quelli pubblicati nei Proceedings “7th Congress of the Romanian Society of Ultrasound in Obstetrics and Gynecology - 2019”

Per acquistare i Proceedings clicca qui.

Contribution selected by Filodiritto among those published in the Proceedings “7th Congress of the Romanian Society of Ultrasound in Obstetrics and Gynecology - 2019”

To buy the Proceedings click here.