Ethical standards in consenting for surgical procedures

Abstract

Surgical procedures have a wide range of risk with potentially life changing implications or even death. Consenting is a patient’s fundamental right and part of medical practice, both from the legal and ethical stand point, as a ‘duty of care’.

Patient consent for surgery can be given or withheld. In exceptional circumstances (urgent lifesaving procedures) it can be completed and signed by the surgeon in the best interest of the patient, but never bypassed.

In line with ethical principles, the patient must be given all the specific information needed, adapted to their understanding, to help make their decision. It should include: indication, alternatives, benefits, expected postoperative progression and potential complications. In addition, consent must be given voluntarily by the patient assessed to have the mental capacity to do so.

In order to obtain a wider perspective of practice, we compared and analyzed the current process of consenting for surgery in three European hospitals with similar profiles: general and emergency surgical public health service providers, in Romania, United Kingdom and Spain.

We observed a wide variety in practice and principle from very general consent, without specifying the procedure and risks particular to each patient, to personalized and detailed information given through timely discussion.

No one system was found to be ideal. The institutional support varied widely as did the application of ethical principles.

The authors note the need for uniform legislation across Europe where practice can reflect key principles to ensure patient rights and best care.

Tablet of Contents:

1. Introduction

2. Method

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

1. Introduction

Consenting to medical treatment or a surgical procedure is the principle that a patient or their representative must give permission prior to receiving any treatment, test, or examination. It is a crucial part of medical ethics and human rights law and the consequences of neglecting this principle are open to litigation.

Consent, as it is currently understood, is a relatively new practice, introduced in the latter part of the 20th Century [1] and comes about as a result of the shift from a more paternalistic approach in the patient/doctor relationship to a patient-centered ethos.

What are the ethics of consenting?

For consent to be valid, it must be voluntary and informed, and the person consenting must have the mental capacity to understand and process information with regard to their treatment, possible complications and the consequences of no treatment, before making a decision whether to accept or refuse.

The principles and values of Medical Ethics

The ethics for consenting is derived from the moral philosophy on which current medical ethics are chiefly based, which are the four key principles of autonomy, non-maleficence (‘first, do no harm’), beneficence (doing ‘good’ to others/acting with the best interest of the other in mind) and justice [2]. Although these are not exclusive, they are considered to be the main standard to measure against. These principles may be elaborated upon to incorporate the core values of: showing respect for human life; making the care of the patient the first concern; treating patients as individuals and respecting the patient’s dignity [3].

The individual patient’s ‘quality of life’ can be seen to be implicit in these values. Clearly

the purpose of these principles and values is to reinforce that individual patient care should be at the centre of health care (not the patient’s symptoms), and the patient has the power to choose what treatment they do or do not wish to receive.

Competing factors in common practice

An important issue when translating principle into practice is that the principles themselves are not always complimentary. Autonomy (self-determination/personal choice) can be at odds with professional opinion, the interpretation of “primum non nocere” and the utilitarian element of beneficence.

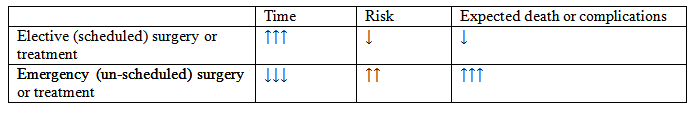

Other factors which might work against ethical principles are such practical issues as time and patient expectation. Procedures which are generally considered more ‘straight forward’ clearly have fewer variables and lower risks to consider than complex or life changing/threatening surgery. The process of gaining consent from a patient in a medical emergency situation gives the patient little to no time to explore the implications and with the reduction in time comes the increase in risk. Therefore, these patients may have lower expectations of their options and outcomes and feel a pressure to consent.

Resources too might have a real or perceived impact on options and choice. Furthermore, where the patient is ‘assessed’ to be incapable, or in exceptional circumstances (urgent lifesaving procedures) their autonomy is given over to a third party, in some cases the surgeon, to decide in ‘the patient’s best interest’.

Finally, the deterrent of legal proceedings could have a real impact on how a patient is treated.

This can be summarized as follows (Table 1):

In addition to such practicalities, the current move from paternalistic or authoritarian attitudes to patient autonomy or the ‘patient-centred’ approach is not something that is as yet deeply embedded everywhere and the responsibility to promote and adopt this lies not only with the institutions and professionals but also with the patients themselves.

How possible is it then to maintain ethical standards and ideals within the varied practical settings and scenarios? How are the aspects of ‘informed’ and ‘voluntary’, fundamental to the decision-making process, interpreted?

This is a topic that has been approached from many different viewpoints and our aim is to examine and compare the practice of gaining patient consent within 3 different European countries in order to try and answer these questions.

2. Method

We gathered and compared information in the form of patient consent documentation and practice guidelines from lead bodies and from each institution for Romania, Great Britain (GB) and Spain and also compared experience of implementation in practice from amongst the authors.

For our comparative analysis we selected 3 hospitals with similar profiles in each country – general and emergency surgical public health service providers – and focused on consent in relation to surgical procedures in mentally competent adults.

3. Results

Overall, we observed a wide variance in practice. Documentation ranges from that which is produced by the individual hospital with no direct or specific guidelines from national statutory bodies (in Romania), to that which is standardized across the public health service by the Spanish Association of Surgeons (AEC) and documentation based on lead body recommendations and standardized across the NHS but designed separately by each hospital (GB NHS Trust).

Figures 1, 2, 3 – Consent forms

The information content also varies from general, non-surgically specific (In Romania) and pre-typed (in Spain) but specific for procedure, to fully personalized (in GB) by the operating team. The general information form in Romania does not allow specifically for additional details to be added by the surgeon or patient and does not cover options, benefits and risks.

Lead body produced forms in Spain, approved subsequently by the hospital which puts them in practice, are designed separately for each of the main surgical procedures, with pre- printed information covering the main surgical details, options and risks in relation to the specific procedure. There is some provision for the surgeon to add comments and to make the form more specific to the patient, hospital or surgeon’s profile. The same form is used for all patients, regardless of age and capacity.

Personalized documentation in GB (lead body-based recommendations, NHS standardized but branded by each hospital) has sections left open to be completed in relation to each individual patient’s case – type of surgery and anesthesia, any possible additional procedures which may be necessary, risks and benefits. This documentation is separate from that used for patients who lack mental capacity and for children and young people.

The process for consenting patients varied most in scheduled surgery. When it takes place ranges from: in Spain at the point of putting the patient on the waiting list (anything up to 6 months prior to surgery and therefore not necessarily by the surgeon who would perform the procedure) and revising on the day of surgery; to, in Romania, at the point of admission; and in GB, on the day of surgery, even if full details are discussed and recorded with the patient mainly before they go onto the waiting list and supporting information given and recorded, including an explanation as to the purpose of surgery, risk and benefits. This is then revised on the day of surgery by a member of the operating team before the patient signs to consent.

Less common in practice here is signing the consent in clinic sessions, reviewing and resigning on the day of the surgery.

In unscheduled surgery when the patient is not capable of consenting or incapacitated, the main difference is in the documentation used-either the same standard form used in all cases (in Romania and Spain) or a separate form in GB, for the surgeon to sign and be witnessed, where a relative or career, legally responsible, is unavailable.

4. Discussion

Medical ethics is clearly a very broad and complex topic and an area for much debate. This article takes only a small segment (practice in gaining consent for surgery) in order to illustrate and examine how wide the interpretation of principle is, and highlight some of the factors which influence this interpretation. Although it touches on the legal implications, it does not explore the law per se governing consent for medical treatment and neither does it go into the issues relating to mental capacity, as these are complex topics on their own.

Romania, Spain and GB were the subject of our investigation based on the fact that these countries have sufficient geographical, cultural and religious diversity from one another whilst, at the same time, are all governed by European Union regulations currently, thus assuming some degree of homogeneity.

It is clear from our investigation that, of the three countries, the process of consenting in GB is the strictest in putting into practice the ethical principles outlined. The General Medical Council (GMC) and The Royal College of Surgeons (RCS) provide Guidelines and standards for surgeons [4, 5] and the NHS for patients [6], to support the process. How this is implemented is not without problems however. In an audit carried out in two large District General Hospitals in England, it was shown that adherence to GMC Guidelines was initially poor [7] and that it was important for staff to have undertaken training to ensure that sufficient information had been given and sufficient discussion taken place for this information to be understood by the patient.

The danger that consenting can be a form filling exercise is a real one. However, the ‘piece of paper’ has a great deal of power. It should reflect and record the options, benefits and risks specific to the patient for whom it is intended not only for the patient’s benefit, but for the healthcare professional also.

Time pressures and timing clearly impact on this. Sufficient time for the patient to consider the options and implications is an important part of the process to ensure consent is valid. Pre- printing as much information in relation to specific pathologies and surgical procedures as possible can help save time and avoid human error. The institutional support provided by the AEC is something that is valued by Spanish surgeons in reducing the vulnerability from the legal point of view. However, the documentation is less specific to the individual patient and their circumstances; it may also appear more intimidating and may not even be read fully by the patient. Since they are not involved in drawing it up, it can be argued that this is not really informed consent. This lack of patient involvement is most true in Romania currently, with less information and time given to the process; however, debates are taking place to bring practice more in line with European standards.

One possible explanation as to why there is a variance in practice is due to a combination of greater patient awareness and the potential link to litigation. Patients theoretically have much more access to information via the internet (and the Press), but with this comes the threat of misinformation and misinterpretation. As a result, greater care is needed to try and ensure that this is redressed by the healthcare professional, especially where patient expectation may be unrealistic.

In a study undertaken by Torjuul et al., [8] it was found that ‘Physicians and surgeons are said to experience a decrease in their autonomy, … because more external factors and stakeholders are influencing their decisions concerning patients’ treatment. They (relatives) almost take for granted that everything can be treated and cured and are more willing to sue physicians for suboptimal results of treatment or deviation from perfect performance...’

Cultural and religious influences shape such attitudes. In Spain and Romania, the family plays a more dominant role in decision making and can often assume responsibility on behalf of the patient, particularly when they are elderly, even when they are mentally capable.

In GB the pressure to follow the principle of patient autonomy, even when it goes against the wishes of the family, could be due to the perceived threat of litigation.

Another factor is the way in which the relationship between doctor and patient is perceived and perpetuated and the real balance of power.

In the consent scenario, the surgeon is the expert as far as diagnosis and prognosis is concerned, however this should be balanced against the patient’s moral right to decide what action to take with regard to their treatment. The surgeon must endeavor to be as impartial and fair (justice principle) as possible, whilst being practically responsible for initiating the task of seeking consent. The patient on the other hand, is expected to exercise their right and autonomy in a situation where they are more likely to feel vulnerable and disempowered [9].

The extent to which culturally this ideal is embraced and supported can be seen in the three different approaches, but even in the best-case scenario, the extent to which consent is truly voluntary is extremely difficult to assess.

A recent landmark legal case in GB ruled: ‘... doctors are no longer the sole arbiter of determining what risks are material to their patients. They should not make assumptions about the information a patient might want or need but they must take reasonable steps to ensure that patients are aware of all risks that are material to them.’ (UK Supreme Court- Montgomery vs. Lanarkshire Health Board). In this case, the Supreme Court rejected a clinician-centered and paternalistic approach to consent, in favor of patient autonomy.

The decision has had great significance for clinical negligence cases in GB [10] and as a result, guidelines in consenting have been revised.

The GMC states that in addition to giving patients the information they want or need in a way that they can understand, including all options, risks and benefits of a treatment, the healthcare professional has a responsibility to answer honestly any other questions or concerns the patient may have. Where the patient does not want to know about these options, basic information should be provided. And it must be formally noted where a patient refuses information.

These measures are steps to making documentation more legally water tight. However, care has to be taken that ethics are not reduced to ‘covering your back’ for fear of being sued.

The idea of ‘Consent’ being a form of contract has already been proposed [11], but it is not without dangers. It can lead to de-personalization and the move to a coverall.

With regard to the patient being informed, it is not necessarily just a case of how much or the type of information given. What is important is the ‘relationship’ that is established between patient and in this case, surgeon, in order to have effective communication, to help the patient understand and engage meaningfully; and this introduces the element of trust into the proceedings.

Trust relies on virtue ethics; that the moral character of the person is good and they do not intend to harm or are bound by a high moral code. This is the human element which translates the principles into best practice and it is a vital element when faced with emergency and/or life-threatening situations.

This paper is one starting point for further investigation as to the value of the consenting process. Other aspects that could be pursued from our initial investigation are the practice in consenting in relation to mental capacity [12] the quality of completed documentation and discussion with patients and health care professionals about their experience of the process [13, 14].

5. Conclusions

Medical ethics are universal. It would be a start to have uniform legislation, at least across Europe, in order for practice to reflect key principles and ensure patient rights and best care.

However, perhaps the whole idea of ‘gaining patient consent’ is the wrong emphasis. It implies that this is the ultimate aim and therefore is vulnerable to coercion of the patient and/or is in danger of being manipulated to meet legal requirements.

Morality is the basis for ethics and morality is about behavior and we should constantly assess our behavior to ensure it is valid and reliable.

The Authors:

SOCEA Bogdan [1]

PĂDURARU Mihai [2]

BETETA Alberto [3]

MORENO-SANZ Carlos [4]

PAWELEC Krystian [2]

CONSTANTIN Vlad Denis [1]

[1] University Emergency Clinical “St Pantelimon”, Carol Davila University of Medicine, Bucuresti (ROMANIA)

[2] Milton Keynes University Hospital NHS Foundation Trust (UK)

[3] Hospital General de Tomelloso (SPAIN)

[4] Hospital Mancha Centro, Alcazar de San Juan (SPAIN)

Contributo selezionato da Filodiritto tra quelli pubblicati nei Proceedings “13th National Conference on Bioethics with International Participation - 2018”

Per acquistare i Proceedings clicca qui.

Contribution selected by Filodiritto among those published in the Proceedings “13th National Conference on Bioethics with International Participation - 2018”

To buy the Proceedings click here.