Competition and Economic Growth in Eastern Europe

Abstract

Competition is the essence of the modern economy. In this paper we construct a series of models with the purpose of showing the connection between certain key measures of competition, as outlined in the Global Competitiveness Report, and economic growth. To this purpose we have constructed three models, and validated them using a panel data methodology.

Our results show that the countries in Eastern Europe are still in their development stages and their economies are mostly factor driven. Improvements in the areas of: infrastructure, quality of institutions, macroeconomic stability, and education should have the highest impact in the immediate future.

Table of contents

1. Introduction

2. Literature review

3. Data and methodology

4. Results and analysis

5. Conclusions

1. Introduction

Competitiveness is a true barometer, a profound and complex notion, playing the role of a critical economic engine for the development of a country, defined as the “ability to generate wealth, wealth or income, or as an ability to achieve economic growth” [1].

According to the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), competitiveness is “a measure of a country’s advantage or disadvantage in selling its products in international markets.” [2].

The paper is structured as follows: we begin with a very brief literature review on the concept of competition and the 12 pillars of economic competition, as outlined by the Global Competitiveness Report.

This is followed up by a presentation of the methodology used in this paper and the results we obtained. The paper ends with a conclusion summing up the paper.

2. Literature review

“Competitiveness emerged in economic theory primarily as a micro concern” [3], this concept was therefore initially reported to the companies’ activity in their chase for profit.

Therefore, Michael Porter “assesses the microeconomic fundamentals of productivity in two areas: sophisticated strategies and actions of companies as well as the quality of the business environment at a microeconomic level” [4]. In a broader approach, “competitiveness is the ability to face competition in the market (through the technological level and the volume of sales)” [3]. Country reporting requires a more complex approach that ultimately aims at “raising the standard of living and welfare of its citizens” [3].

Macroeconomic reporting implies the competitiveness of a particular country by simultaneously fulfilling these conditions:

- “productivity increases at a rate that is similar to or superior to that of major trading partners with a comparable level of development;

- manages to maintain an external trade balance in the conditions of a free market economy;

- achieve a high level of employment.” [3].

The “Global Competitiveness Report” published by the World Economic Forum is a highly relevant publication in regards to the measurement of those specific factors that contribute to sustainable development on a worldwide level.

Due to the fact that competitiveness is deeply anchored in the economic environment and is vital when establishing a country’s economic policies as well as investment decisions by various stakeholders [5], it is of great importance that decision makers analyses the situation of their country and how it is situated in comparison to other countries.

According to the Global Competitiveness Report competitiveness is “a set of institutions, policies, and factors that determine the level of productivity of an economy” [5], thus having a strong relevance for an economy’s prosperity and welfare.

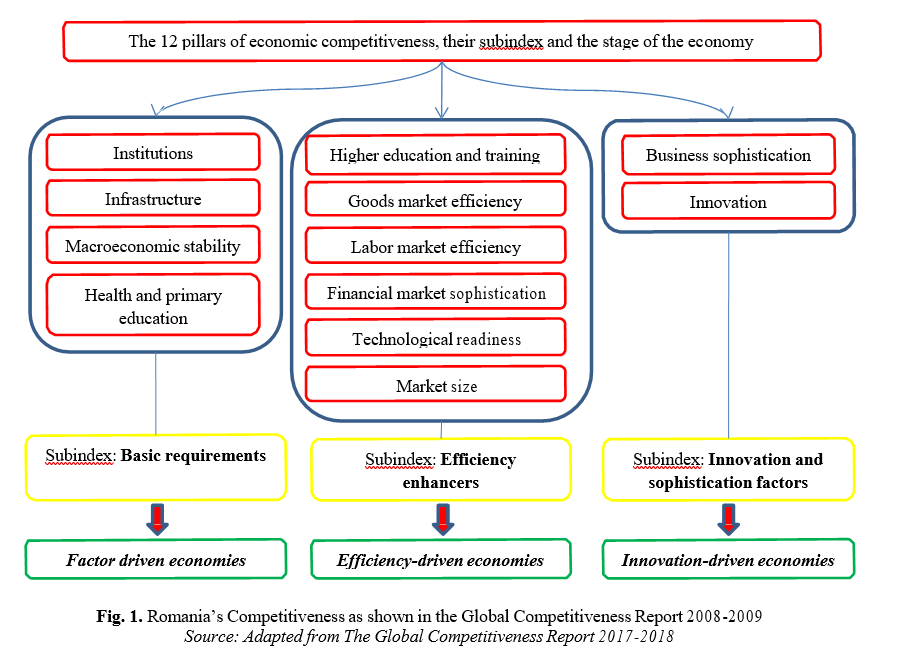

The current methodology combines 114 indicators relevant to prosperity and productivity, grouped into 12 pillars, then into 3 sub-indexes [Fig. 1].

The 12 pillars of competition are presented below.

Institutions: there are various interactions between entities such as individuals, firms or governments that aim to generate income and, implicitly, wealth in the economy.

The legal framework is not the only relevant element in this equation, but also the approach of the Government regarding the market itself, the liberties (freedom) and the efficiency of operations.

Thus, parameters such as excessive bureaucracy, corruption, overregulation and lack of honesty, lack of transparency, etc. become relevant.

Infrastructure: is important because it is seen as a facilitator of competitiveness that can play a decisive role in the location (placement) where specific activities (or sectors) can develop in certain economies.

This pillar can play an integrating role for the various economies, the distance between countries and regions not forming a barrier in the way of their connection.

The transport networks created can be facilitators for entrepreneurs (e.g., transport of goods) but also, for labor mobility.

Macroeconomic stability: is vital to the prosperity of businesses (by, for example, making informed decisions when market conditions are turbulent) and, implicitly, to the degree of competitiveness of the country.

Health and primary education: the physical well-being of the workforce enables them to effectively reach high productivity by reaching their potential much easier; indirectly, a good physical condition acts as a psychic facilitator. Basic education is the other ingredient in increasing the efficiency of each worker.

Higher education and training: these two elements allow the development of production systems (production processes) with greater ease and enable man (in general) to accommodate more easily the changing, often turbulent context. Workers’ skills must be developed, including in terms of particular elements (niche) through appropriate training programs. Here, critical measurement factors are “secondary and tertiary enrollment rates” and the “quality of education as assessed by the business community” [6].

Goods market efficiency: Efficiency in this market is described by the appropriate adjustment of the mix of products and services, in line with the two main forces acting (operating) on the market: demand and supply. A healthy competition for companies is needed because it can stimulate the high degree of satisfaction of consumers’ needs (that are becoming more and more complex, sophisticated) both on domestic and foreign markets.

Labor market efficiency: As is the case with firms of different sizes, as well as the broader economic context, the flexibility and efficiency of the labor market is closely related to the allocation of workers in the right places (thus, using them efficiently in the economy), and their work needs to be stimulated (financially or morally) accordingly to their efforts and productivity.

Financial market sophistication: Effective use of financial sector resources refers to productivity in a sense that is directed to those projects (entrepreneurial or investment projects) with a high degree of return on investment (biggest rates of return), calculation associated with a certain degree of (assumed) risk that is particular for any project. The global financial crisis demonstrates the relevance of this pillar.

Technological readiness: This pillar portrays the extent to which an economy manages to adapt technology in order to increase productivity. Thus, the central element becomes information and communication technology. In measuring this pillar, the country in which these technologies were developed is not relevant, but the companies’ access to (advanced products, blueprints) them (and their ability to use them).

Market size: As the size of the market increases, it allows certain companies to exploit (more easily) the concept of economies of scale. Globalization allows international markets to become substitutes for domestic one. Market size is measured “by including both domestic and foreign markets” [6].

Business sophistication: The relevant elements embedded in this pillar are the quality of a country's business networks and the quality of each company’s operations and strategies. These increase the efficiency of production and quality of service delivery. This increase in productivity leads to amplifying the competitiveness of a country.

Innovation: Addressed as a distinctive element to technology, innovation is linked to the expansion of the knowledge horizon, and implies the existence of favorable conditions within a country (both public and private sectors), that act as facilitators for innovative activities in order to gain competitive advantage. Research and development is in the center of investments, allowing countries to create “cutting-edge products and processes to maintain a competitive edge”. Also, there is a strong need for “the presence of high-quality scientific research institutions, extensive collaboration in research between universities and industry, and the protection of intellectual property” [6].

3. Data and methodology

The main objective of this paper is to analyze the relationship of formed between competition on the market between different companies and economic growth in developing nations.

To this purpose, we used the data available in the aforementioned Global Competitiveness Reports in order to get a measure of the level of competition in different countries and we linked it with GDP per capita, as a proxy for economic development.

The competition data was obtained from the annexes of the reports for the period 2008 to 2016. The GDP data is measured in 2010 US dollars, for the same period, and was obtained from the World Bank.

We decided to focus our analysis on Romania and relevant neighboring countries, as such, the data we took into consideration is for Romania, Bulgaria, Hungary, Moldova, Serbia and the Ukraine.

The investigation is based on a panel data methodology.

Because of the high degree of correlation between some of the variables, instead of having an overall look at the effects of competition, we split the model into three separate models: factor driven, efficiency driven and innovation driven economies.

In the case of efficiency driven, after the initial analysis, we found that multicollinearity is an issue because there is a high degree of correlation between market size and higher education (0.73).

We decided to construct two separate models, with each variable considered separately.

We applied the Breusch-Pagan Lagrange Multiplier test and the Hausman test and found that the random effects model is recommended for basic economic drives and fixed effects for efficiency and innovation economic drives.

4. Results and analysis

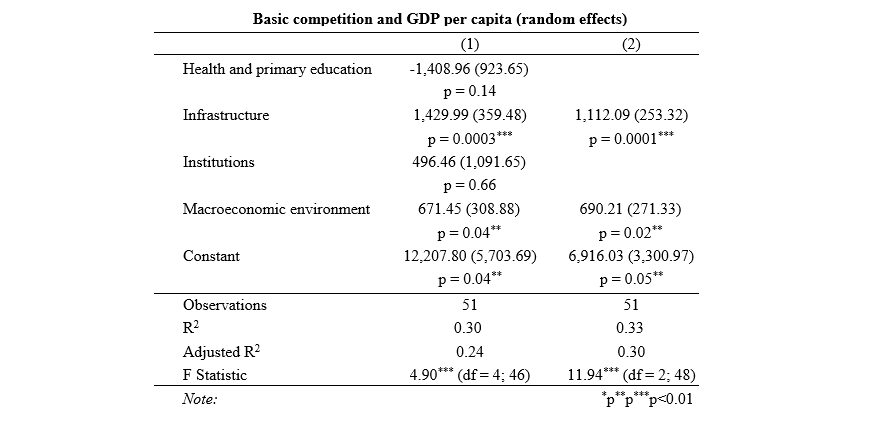

The first model taken into consideration is the basic model. The dependent variable is the GDP per capita, while the dependent variables are: health and primary education, infrastructure, institutions, and the macroeconomic environment.

First of all, the R2 value, for both models are around 0.3, which means that around 30% in the variation of GDP can be explained by the independent variables, which, while not a very high value, is to be expected.

That being said, out of the four variables initially chose, only the macroeconomic environment and the infrastructure have a statistically significant impact on GDP.

This initial result confirms that improvements in the infrastructure of the country or the macroeconomic stability will lead to economic growth, for the countries in the sample.

This is significant due to the fact that it shows most of these countries still have a relatively limited level of economic development and can stand to benefit significantly from these types of improvements.

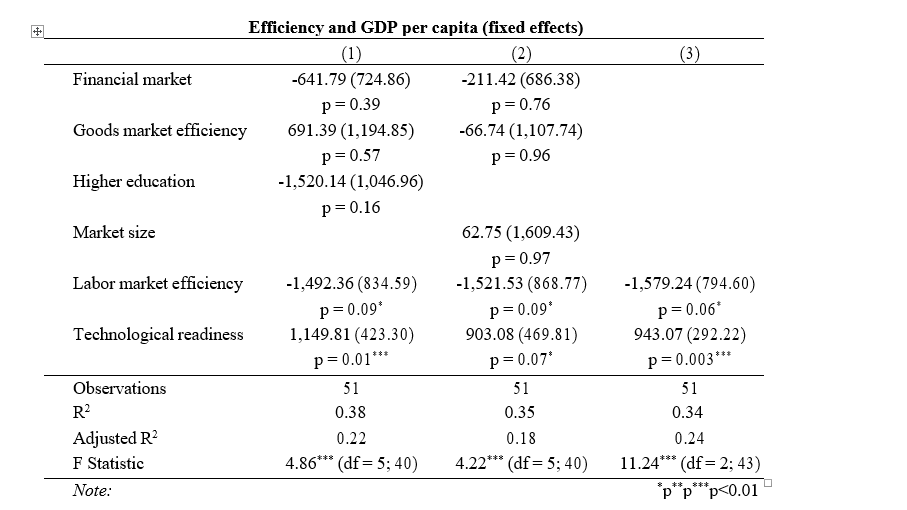

The second model taken into consideration links economic growth and competition factors specific to countries where growth is driven primarily by improvements in efficiency: financial market, good market efficiency, higher education, market size, labor market efficiency and technological readiness.

As mentioned before, higher education and market size are highly correlated and, in order to ensure thoroughness, we considered both cases (1 and 2 from below). We can see that they do not significantly influence the final outcome.

By far the most unexpected result, in the above table, is the fact that there seems to be no statistically significant relationship between higher education and economic growth.

The absence of such a link in the cases of the variables: financial market, goods market efficiency, or market size, with labor market efficiency being accepted at the 10% level but rejected at the 5%, is also an issue, but much less so than education.

However, when taking into consideration the evolution of GDP and higher education, for the aforementioned countries, over the years with available data, GDP has had significant increases in most of these countries, whereas higher education has remained at the same level throughout.

As such, we can assume that this situation is encountered not so much because the education does not contribute to economic development, but mostly because these countries have had a fairly high level of education, which has not increased over this period, while GDP has increased due to other considerations.

From model 3, we can see that, out of all the variables taken into consideration, technological readiness has a positive impact on economic growth.

The model has an R2 value of 0.34, which shows that it only explains 34% in the variation of the dependent’s variable, GDP. A fairly low value given that we initially expected the countries to be efficiency driven, with a much higher R2 than that encountered for basic economic drives.

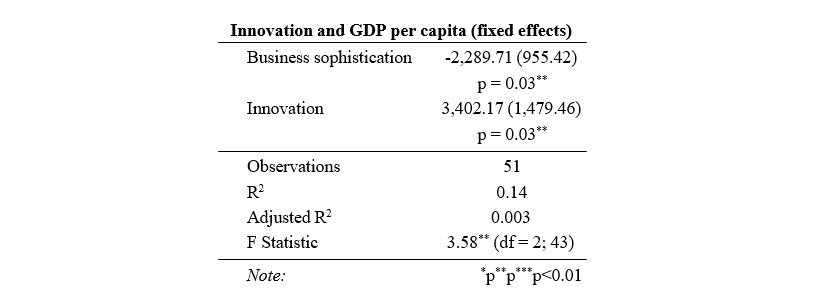

The third model we took into consideration is a measure of the impact that innovation has on the evolution of economic growth in a country. The variables taken into consideration are Business sophistication and Innovation.

The results of the third model are somewhat expected, given the previous discovery that these countries have a more limited level of economic development.

Both variables are statistically significant, however, the models itself isn’t very good. The R2 value is only 0.14 and the adjusted value is 0.003, which means that these variables explain virtually nothing in the evolution of the dependent variable.

5. Conclusion

In this paper we have analyzed the connection between competition and economic growth in Eastern Europe. The data taken into consideration is for the period 2008 to 2016 and the countries: Romania, Bulgaria, Hungary, Moldova, Serbia and the Ukraine.

We have constructed 3 panel data model which link GDP per capita, as the dependent variable, and the 12 pillars of economic competition, split in three sub-indexes, as independent variables.

The first model showed that infrastructure and macroeconomic stability are the main drives of economic growth for countries in Eastern Europe. The results of the second model were more surprising.

We found that technological readiness contributes to economic growth, but higher education does not.

We assume that this is because the GDP of these countries has changed significantly over the past decade, whereas other variables, such as higher education of quality of institutions, have not.

A more in-depth study with a broader scope in terms of countries is required in order to properly clarify this issue.

The third model was rejected on accounts that the R2 value is very small, only 0.14, and that means that the impact of these variables is limited at best.

Overall, we can say that the economies of countries in Eastern Europe are still mostly factor driven, with a very transition being made towards efficiency drive economies.

It is expected that other variables will become much more important in the near future.

Contributo selezionato da Filodiritto tra quelli pubblicati nei Proceedings “International Conference on Economics and Administration - 2018”

Per acquistare i Proceedings clicca qui:

http://www.filodirittoeditore.com/index.php?route=product/product&path=67&product_id=149

Contribution selected by Filodiritto among those published in the Proceedings “International Conference on Economics and Administration - 2018”

To buy the Proceedings click here:

http://www.filodirittoeditore.com/index.php?route=product/product&path=67&product_id=149