The Role of the Monarch as Head of the State in the Contemporary Era

Abstract

In the contemporary era, the constitutional monarchies are combined with a prominent representative democracy with an elected or hereditary monarch as head of the state. The modern constitutional monarchies are using the separation of powers in the state, where the monarch is chief executive and legislator, or only has a representative role. The major objective of this work is to research what could be today the role of a monarch in a constitutional monarchy. This form of government represents two major advantages: it ensures, in particular, a special stability at the top of the political-administrative system and the function of the head of state is de-politicized to a higher degree. However, the fruition of this privilege is due to the monarch’s professionalism, to the righteousness of the monarchy and to the will of the politicians to or not to deal with the problem of the monarchy.

Table of Contents:

1. Introduction

2. The state and the monarchy as form of government

2.1 The function of the state

2.2 The monarchy as form of government

2.3 The monarch as head of the state in the contemporary era

3. Comparative analysis on the constitutional monarchies from Europe

3.1 United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland

3.2 Kingdom of Denmark

3.3 Kingdom of Belgium

3.4 Kingdom of The Netherlands

3.5 Kingdom of Spain

4. Synthesis of the analysis and conclusions

1. Introduction

In the contemporary era, the constitutional monarchies are combined with a prominent representative democracy with an elected or hereditary monarch as head of the state. The modern constitutional monarchies are using the separation of powers in the state where the monarch is chief executive and legislator, or only it has a representative role.

The aim of this paper is to research what could be today the role of a monarch in a constitutional monarchy. This type of government represents two major advantages: it ensures, in particular, a special stability at the top of the political-administrative system and the function of the head of state is de-politicized to a higher degree. However, the fruition of this privilege is due to the monarch’s professionalism, to the righteousness of the monarchy and to the will of the politicians to or not to deal with the problem of the monarchy.

The comparative analysis of the paper will start the history of the constitutional monarchy in the European countries and will research which are the powers of the head of state in the constitutional monarchies from the Europe countries. How important are these powers and in which situations they could count and could be used?

2. The state and the monarchy as form of government

The entry into the third millennium has been accompanied by a number of transformations at the level of the whole statue, by being set up in a great state of the art of every country in Europe and in the world. History has brought the states of the world into a new situation.

The state has a suffered a complex, costly, and long-lasting process of transformation which it is completed, and the state, defined as the highest organization of righteousness, has a reasonable mission to try and guide the path to the natural evolution. In its essence, the state has remained a power and an authority renowned and accepted by members of the society. It is the guarantor of order and legality and ensures the protection of rights and freedoms of its citizens [1].

Today, sovereignty has remained a strictly state-related notion, the state being the only one to be subject of law and in the same time subordinated to the international public law rules.

The Westphalia model of sovereignty remains the basis of a modem state, having its basses on the concepts of territoriality and sovereignty, renegotiated and redefined within the frameworks and structures of change of the regional and global organizations.

Like, in the case of sovereignty, there is a transfer of the functions of the frontiers of the national state to the external borders of the regional organizations (like European Union), in order to strengthen the latter's sovereignty. Therefore, the border no longer has the role of an intangible territorial limitation, the state being inevitably becoming a part of a whole within the free circle of goods, services, information, and culture. In this enlarged area – the- European Union – the citizens of a state have completed their national citizenship with the European citizenship, enriching their landscapes and obligations. In the constellation, the sphere of life brings new nuances, mutations to the state must provide them with the organized development, evolutionary framework.

Taking into consideration these new aspects of the contemporary era, it can be states that the new role of the state is offered to the state is to be an active subject the supranational level, in regional political institutions and in intergovernmental organizations. For that, here it is important to be underlined which are the functions of the state.

2.1 The function of the state

The state has the following functions [2]:

• the legislative function is the exertion, the direct manifestation of the sovereignty of the city, and the fact that the state establishes binding rules of union and that it should be brought to the attention, in the event of their instigation or inconsistency, of the power of coercion that only the state has. The state transforms into law any human-related solution necessary for the economic and social development, the maintenance of the order of the people and the assurance of the social order;

• the executive and administrative function is to organize the organization and the elaboration of laws, to ensure the functioning of the public services set up in this area, and to develop normative acts based on the laws;

• the judicial function has as its objective the solving of the legal issues and the creation

of laws, as well as the surveillance of the law’s compliance;

• the external function of the state refers to the attributions developed by the state for the development of relations with other states on the basis of international relations, as well as for the distribution to the international bodies in order to solve the problems of the national, national and global general sentiments of mankind.

In order to accomplish its functions, the state organizes a system of institutions (bodies) Thus, each of them has a different category of state organs: legislative bodies (Parliament, National Assembly, Congress et al.); executive councils – the executive organs, they are represented by the head of state, the head of government, the government; judiciary bodies – judges and other judicial institutions.

The form of government designates the way in which the state’s bodies and institutions are constituted and are functioning [2, p. 80]. The notion of form of government has a legal significance but the significance of the notion should not be reduced to legal proceedings.

The forms of government, the manner in which they are organized in the state, have numerous implications of historical, social, political and economic nature.

The various forms of government can succeed in the state structure and vice versa. It is here that the constitutional elements and the choices in the country are performed by the head of the state. It also targets the rations established by the classified as head of state and other categories of bodies, especially the parliament and the government [3]. Regarding the form of government, the states can be divided in two categories: republics and monarchies [4].

2.2 The monarchy as form of government

A monarchy in a strict sense of term is a state ruled by a single absolute hereditary ruler [5].

The monarchy is a form of government where as head of state is a hereditary or designated monarch (king, prince, emperor, emir), in accordance with the traditions of the constitutional regime [4, p. 47].

In modern parlance the notion of monarchy is generally used for a polity with a hereditary head of state. The only exception in contemporary Europe is the papacy. A republic, on the other hand, is in this parlance a polity without a hereditary head of state [6].

Though the monarchy has historically indicated absolute power, the concept has become increasingly diluted with the evolution of democratic principles. Today, some monarchies exist but are merely symbolic, whereas others coexist within constitutional structures.

Historically, the first step to a constitutional monarchy was the adoption of Magna Carta which, among other provisions, it contained two basic principles for the institution of monarchy. The first principle required that the sovereign rules according to the law and to make himself accountable for the way in which he should reign. The second principle was that the rights of individuals took precedence over the personal wishes of the sovereign [5].

The constitutional monarchy is characterized by the limitation of the monarch’s powers by the fundamental law of the state (the Constitution). The monarch, still have some powers however, to dissolve the Parliament, to organize new elections, has the opportunity to reject the laws voted by the Parliament [2, p. 80].

Monarchy was the most common form of government in the history of humanity. Until the 19th century, the monarchy was the most common form of government in the world.

In our days, 45 nations in the world are governed by some form of monarchy. In many cases, this monarchy is largely symbolic and subservient to a constitution, as with the 16 commonwealth states recognizing Britain’s Queen Elizabeth II. By contrast, monarchies continue to enjoy far-reaching political authority in Brunei, Liechtenstein, Monaco, Morocco, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, and Swaziland [Tomar, D. 20 Common Forms of Government Study Starters, https://thebestschools.org/magazine/common-forms-of-government-study- starters/#monarchy, accessed 10.03.2019].

2.3 The monarch as head of the state in the contemporary era

The executive power is represented by the head of state and head of government. The earliest is one of the oldest righteous authorities. In the course of time, this authority has embraced two forms of manifestation: a collegial form materialized by a council, presidium if the council, state council, another by a unipersonal form, represented by the king, sultan, sultan, gentlemen, or president.

And, in this context, it is very important to understand the evolution of the institution.

Thus, the mono-cephalous model of the head of state is specific to the absolute monarchy and to the presidential system, where the head of state is also the head of the government.

The bi-cephalous model takes into account the dual (hereditary or elective) monarchy, as well as the semi-presidential system, where the head of state carries out its duties together with other organs: the prime minister, the government.

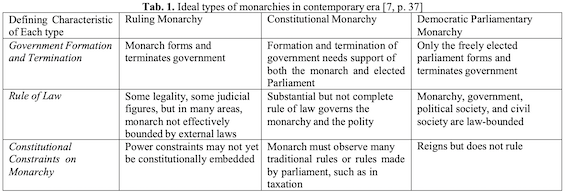

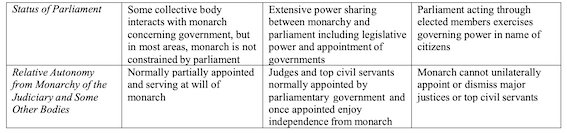

The head of state has and more symbolic attributions like the role of representation ore other attribution in government as we can distinguish between “ruling monarchy”, “constitutional monarchy”, and “democratic parliamentary monarchy” [7].

The defining characteristic of a democratic parliamentary monarchy is that only the freely elected parliament forms and terminates the government. In a constitutional monarchy, by contrast, there is a strong element of dual legitimacy in that parliament and the monarch need each other’s support in order to form or terminate a government. In still greater contrast, in ruling monarchies the monarch can often unilaterally form or terminate the government [7]. In fact, seven of Western Europe’s sixteen democracies with populations of a million or more are monarchies: Belgium, Denmark, the Netherlands, Norway, Spain, Sweden, and the United Kingdom.

The three types of monarchies presented in the Tab. 1 have its own set of patterns

concerning the rule of law, constitutional constraints on the monarch, the status of parliament, and the relative autonomy of the judiciary. Tab. 1 should make clear how the role of the monarch changed by time, indicating the differences between ruling monarchies, constitutional monarchies, and democratic parliamentary monarchy. As being ideal-types of monarchies, we have to mention, that today we find a mixt between these three types, especially the last two.

3. Comparative analysis on the constitutional monarchies from Europe

As already stated above, the methodology of this study will be mainly qualitative and it will be based bay analysing the main attributions and powers of some states from Europe that have as form of government, the monarchy. The research will be conducted by the study of the constitutional laws and in some cases of the doctrine, starting from the assumption that every state establishes its type of organization and exercise of power in the Constitution, considered to be the country’s fundamental law, the supreme law, the fundamental pact.

Every modern state has a Constitution because, in the rule of the law, the government exercise their power only by virtue of certain prerogatives established by a political-legal act, of an act by which they are invested with certain responsibilities.

The Constitution is therefore the source of the political system, as well as of the latter’s framework within the national legal system [8].

3.1 United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland

In the British system there is a distinction between the idea of the ‘crown’ and the ‘monarchy’ called. The ‘crown’ is non-personal juridical concept, summing up all the rights, including the powers of the executive. This is how it is explained in the specialty literature that “The king is by nature and by law more mortal man. But the Crown became impersonal, immortal, a symbol of the final unity and the continuity of the government attributions” [9].

The monarch in Britain has the following duties:

• Appointment of the Prime Minister. The monarch appoints the leader of the party that won the general election. It is also up to the crown to nominate to the high positions in the ministers, judges, officers in the armed forces;

• Giving royal assent of the Bills of the Parliament;

• Presents the ‘message of the throne’ at the state opening of Parliament, which is an argument in favour of the governmental program, and it is written by the prime- minister;

• Granting orders and distinctions;

• Names judges and agree pardon;

• Dissolution of the Chamber of Commons. It is the traditional established by costume rules that the monarch dissolve parliament. In the present, the initiation of the dissolution of the Parliament it is initiated the Prime Minister;

• Declaring the state of war and concluding the peace;

• Signing the international treaties;

• Recognizing other states and governments.

The monarch has some prerogatives regarding the appointment of the prime minister. In the past, there have been monarchs with a prominent role in the appointment of the prime minister. Thus, in 1834, William IV dismissed Lord Melbourne and instructed Sir Robert Reel to form the Cabinet, although he had a quarter form the majority of the deputies [5].

In our present days this power it is limited to the fact that a party wins the majority in the House of Commons, its leader becomes automatically prime minister, and the government is defeated in elections, the monarch must appoint the head of the government the leader of opposition.

The monarch has a certain influence on the ground to appoint ministers, although this is not decisive. He also dismissed the Government by the dismissal of the prime minister. Such a situation has not yet occurred since 1834. The British doctrine is not unanimous in appreciating that the sovereign has the power dismiss a government which is acting in a non- constitutional way.

The monarch is likely to dissolve the Parliament, but it does not take effect without an endorsement, a resolution of the Privy Council, lead the lord president, and proclamation for which the Lord Chancellor assumes its responsibilities.

In the present the monarch has some exhaustive functions, in certain situations strictly limited, like that of the resignation of the prime minister. Also, in the discussions with the ministers, the monarch has the right to say his own views and to receive information from different fields of the government.

3.2 Kingdom of Denmark

The country is according to the article 2 of the Constitution: a constitutional monarchy. Here royal authority shall be inherited by men and women in accordance with the provisions of the Act of Succession to the Throne [Folketinget, 2013, The Constitutional Act of Denmark, Grafisk Rådgivning https://www.thedanishparliament.dk/, accesse 12.03.2019]. In 1972, Margaret II became Denmark’s first Queen in the last 600 years.

The legislative authority belongs to the Queen and the Folketing (Danish Parliament) conjointly. The monarch has the right to legislative initiative, setting up a number of laws at the Folketing office, and organizing a debate on their edges. In case of emergency situations and when it is imminent to be called the Folketing, the queen can decree temporary laws decrees that cannot be against the Constitution and that should be approved by the Folketing.

The executive power belongs to the Queen which exercises it through its ministries. In this regard, the Queen appoints and dismisses the Prime Minister and the other Ministers. She decides upon the number of Ministers and upon the distribution of the duties of government among them. The signature of the monarch to resolutions relating to legislation and government shall make such resolutions valid, provided that the signature of the King is accompanied by the signature or signatures of one or more Ministers.

The article 12 of Danish Constitution states without doubt that the monarch has supreme authority in all the affairs of the Realm, and exercises such supreme authority through the Ministers [https://www.thedanishparliament.dk/]. This authority can be observed in the fact that she can impeach a minister for maladministration of office. This authority can be observed also in regarding the role played by the monarch in the external affairs and the role of representation.

The Constitution provides that the monarch shall act on behalf of the Realm in international affairs, but, except with the consent of the Folketing, the King shall not undertake any act whereby the territory of the Realm shall be increased or reduced, nor shall he enter into any obligation the fulfilment of which requires the concurrence of the Folketing or which is otherwise of major importance.

Although the Queen has an important role of representation of the country, the queen has not the Power to use the armed forces against a foreign state without the approval of the Folketing.

Other powers of the Queen are:

• Dissolving the Folketing, with the condition that a person swear – in for prime minister before the dissolution;

• Giving Royal Assent to the bills adopted by Folketing;

• Giving the mercy and granting the amnesty;

• The appointment of civil servants according the provisions of the statute.

3.3 Kingdom of Belgium

Article 1 of the Constitution defines Belgium as being a federal state, composed of Communities and Regions. Belgium comprises three Communities: the Flemish Community, the French Community and the German-speaking Community. Belgium comprises three Regions: the Flemish Region, the Walloon Region and the Brussels Region [Belgian House of Representatives, 2018, Belgian Constitution as updated following the constitutional revision of 24 October 2017, Belgian Official Gazette of 29 November 2017].

Belgium has a form of government a constitutional parliamentary monarchy, where the head of the state does not have any attribution in the government, its powers being limited to some aspects of representation and protocol [10].

Regarding the role played by the monarch in the legislative power, The King has the right to convene the Houses to an extraordinary meeting and he pronounces the closing of the session. The federal legislative power is jointly exercised by the King and by the House of Representatives for: the granting of naturalization; laws relating to the civil and criminal liability of the King’s ministers; State budgets and accounts, the setting of army quotas.

The King can adjourn the Houses. However, the adjournment cannot be for longer than one month, nor can it be repeated in the same session without the consent of the Houses. The King has the right to dissolve the House of Representatives only if his House, with the absolute majority of its members: either rejects a motion of confidence in the Federal Government and does not propose to the King, within three days of the day of the rejection of the motion, the appointment of a successor to the prime minister; or adopts a motion of no confidence with regard to the Federal Government and does not simultaneously propose to the King the appointment of a successor to the prime minister.

Moreover, the King may, in the event of the resignation of the Federal Government, dissolve the House of Representatives after having received its agreement expressed by the absolute majority of its members [Article 46 from Belgian Constitution as updated following the constitutional revision of 24 October 2017, Belgian Official Gazette of 29 November 2017, Belgian House of Representatives, 2018].

The role of the monarch in the executive power regards the attribution that the King appoints and dismisses his ministers. The Federal Government offers its resignation to the King if the House of Representatives, by an absolute majority of its members, adopts a motion of no-confidence proposing a successor to the prime minister for appointment by the King or proposes a successor to the prime minister for appointment by the King within three days of the rejection of a motion of confidence.

The King appoints the proposed successor as prime minister, who takes office when the new Federal Government is sworn in. Also, the King appoints and dismisses the federal secretaries of State. They are deputies to a minister and the King determines their duties and the limits within which they may receive the right to countersign.

The Constitution of Belgium provides for the monarch some powers drawing a role of presentation in international relations for the king. Thus, the King directs international relations, notwithstanding the competence of Communities and Regions to regulate international cooperation, including the concluding of treaties, for those matters that fall within their competences in pursuance of or by virtue of the Constitution.

Also, he commands the armed forces; he states that there exists a state of war or that hostilities have ceased. He notifies the Houses with additional appropriate messages as soon as interests and security of the State permit.

Other powers of the king are:

• Sanctioning and promulgating laws;

• Making decrees and regulations required for the execution of laws, without ever having the power either to suspend the laws themselves or to grant dispensation from their execution;

• Remitting or to reducing sentences passed by judges, except with regard to what has been ruled on concerning ministers and members of the Community and Regional Governments;

• Granting military orders.

3.4 Kingdom of The Netherlands

The executive power belongs in the Netherlands to the King and the ministers, with the difference that the king is not responsible for his own acts, and the ministers are resendable for their own acts. The King appoints and revokes the Prime Minister, as well as the other ministers, with a royal decree. The ministries are established by royal decree and they are headed by a minister.

The ministers are composing the Ministerial Council, which is chaired by the Prime Minister. Here we notice an important difference from the Constitution of Denmark, where the Queen has a role in chairing the meetings of the Council of Ministers.

Regarding the legislative power, the Constitution of the Netherlands give to the King the role initiate laws on his behalf or together with the second lower house of the State’s General (Parliament). At the moment when the law was adopted by both houses of the Parliament, it has to be sanctioned by the king.

Also the king has the role to address Parliament, in which a statement of the policy to be pursued by the Government shall be given before a joint session of the two Houses of the State’s General that shall be held every year on the third Tuesday in September or on such earlier date as may be prescribed by Act of Parliament [Article 65, The Constitution of the Kingdom of the Netherlands 2008, Published by the Ministry of the Interior and Kingdom Relations, Constitutional Affairs and Legislation Division in collaboration with the Translation Department of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs].

In the cases in which there is state of emergency it may be declared by royal decree in order to maintain internal or external security. As in Denmark, the Netherlands Constitution provides that the declaration a war by the King should be authorized by the States General.

Immediately after the declaration of a state of emergency and whenever it considers it necessary, until such time as the state of emergency is terminated by Royal Decree, the State’s General shall decide the duration of the state of emergency.

3.5 Kingdom of Spain

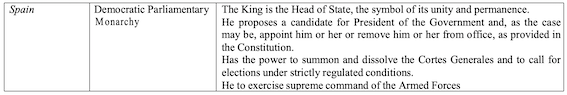

From the point of view of form of government Spain is a monarchy. Like all the contemporary European Monarchies, the Spain monarchy has also a parliamentary character, which means that the powers are belonging to the Parliament and to the Government.

Regarding the role played by the King in the state, it is clearly stated by the Spanish Constitution that the King is the Head of State, the symbol of its unity and permanence. He arbitrates and moderates the regular functioning of the institutions, assumes the highest representation of the Spanish State in international relations, especially with the nations of its historical community, and exercises the functions expressly conferred on him by the Constitution and the laws [Section 56, Constitution of Spain, availble online at: http://www.congreso.es/portal/page, accessed 12.03.2019].

In comparison with other Constitutions where they are monarchies as form of government, the Spanish Constitution clearly stipulates which the attributions of the king by enumerating them in the section 62 [Constitution of Spain, availble online at: http://www.congreso.es/portal/page, accessed 12.03.2019]. Thus, they are the following:

• To sanction and promulgate the laws;

• To summon and dissolve the Cortes Generals (Parliament) and to call for elections under the terms provided for in the Constitution;

• To call for a referendum in the cases provided for in the Constitution;

• To propose a candidate for President of the Government and, as the case may be, appoint him or her or remove him or her from office, as provided in the Constitution;

• To appoint and dismiss members of the Government on the President of the Government’s proposal;

• To issue the decrees approved in the Council of Ministers, to confer civil and military;

• To be informed of the affairs of State and, for this purpose, to preside over the meetings of the Council of Ministers whenever he sees fit, at the President of the Government’s request;

• To exercise supreme command of the Armed Forces;

• To exercise the right of clemency in accordance with the law, which may not authorize general pardons. To exercise the High Patronage of the Royal Academies. Regarding the role of the king in foreign affairs and international relations, it can be observed that he accredits ambassadors and other diplomatic representatives.

The Foreign representatives in Spain are accredited before him. Also, it is incumbent upon the King to express the State’s assent to international commitments through treaties, in conformity with the Constitution and the laws. The King, following authorization by the Cortes Generales, may declare war and to make peace. Regarding the role of the monarch in the legislative power, it can be observed that in Spain, in comparison with the Netherlands or with Denmark, the King has no role in initiate legislation.

The Legislative initiative belongs to the Government, the Congress and the Senate, in accordance with the Constitution and the Standing Orders of the Houses. The only provision in the legislative process regarding the monarch is that the King shall, within a period of fifteen days, give his assent to bills drafted by the Cortes Generales, and shall promulgate them and order their publication forthwith.

4. Synthesis of the analysis and conclusions

From the analyses conducted on some monarchies from Europe in the above paragraphs, it can be observed that the role of the monarch in the contemporary era could be synthetized under three aspects:

• The role of the monarch in some cases in only formal and he plays more representation of the state, having some attribution in the foreign affairs

• The monarch can interfere in the legislative process, in some cases proposing laws.

Here he can play a key role in appointment of gov’ernments.

• He represents together with the army one of the two pillar of the state.

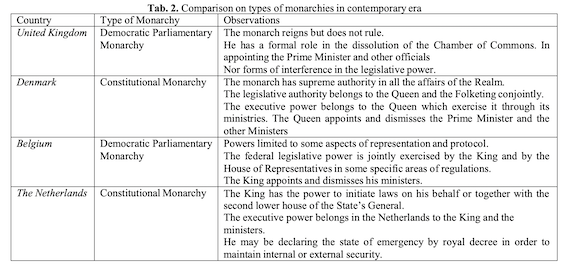

As it can be observed in Tab. 2, from our analysis we could not identify any type of ruling monarchy. All the analysed countries are oscillating between a democratic parliamentary monarchy and a constitutional monarchy. We consider important for our analysis the provision that the monarch has a role not only in the executive power, but also in the legislative power, as the case of Denmark or The Netherlands, where Extensive the power is shared between monarch and parliament and appointing of governments.

Regarding the role of the monarch in the countries from Europe, it can be mentioned that, with some exceptions, they are defined constitutional monarchies, but in reality, they have a mixt of characteristics between constitutional monarchy and democratic Parliamentary monarchy. Even in the clearest Parliamentary democratic monarchy – The United Kingdom, the monarch still has some important role in the legislative or executive power, but, by custom, he does not exercise discretionary these powers, because in most all the case he asks for the approval of the prime-minister or of the parliament.

The institution of the monarch in Europe suffered in the last century a great reduction of powers, the monarch ceases to rule but continues to reign as head of state and the shift is orderly, with royal persons, prestige, and property remaining intact. In the democratic states with this type of form of government, the monarchy lives on as a symbol of the nation, its traditions, and its unity.

Contributo selezionato da Filodiritto tra quelli pubblicati nei Proceedings “6th ACADEMOS Conference 2019 – Political and Economic Unrest in the Contemporary Era”

Per acquistare i Proceedings clicca qui.

Contribution selected by Filodiritto among those published in the Proceedings “6th ACADEMOS Conference 2019 – Political and Economic Unrest in the Contemporary Era”

To buy the Proceedings click here.