Use of Food for Weight Reduction in Obesity Management

Abstract

The increasing prevalence of obesity has led to the approach of various diet-pharmaceutical methods for reducing body fat. The present study monitored the impact of using special nutritional foods for weight reduction on a sample of adults who followed a slimming programme.

Using objective measurements of body mass index, perimeters, percentage of body fat) we evaluated the effectiveness of meal replacements diets in body weight management and the impact in body composition for working age people.

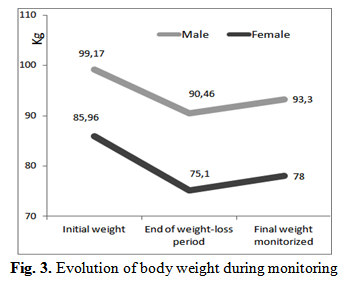

During weight loss programs (3.98±2.29 months), 79 participants (56 women, 23 men) lost an average of -10.19±6.12 kg of their body weight, -11.47±9.15 cm in the abdominal perimeter, -

5.29±3.46 of the percentage of body fat. Subsequently, in the period of maintenance of weight gained, subjects were followed for an average of 11.28±8.1 months and for the entire group of participants was reached an average weight gain of +2.86±3.02 kg compared to the minimum weight (31.5% of weight lost).

Replacing two meals a day was an effective way to lose weight because of its simplicity and convenience of use. Long-term maintenance was better in the subjects that replaced one meal a day, but is still a challenge and required further research. The diets using food for weight reduction can be

promoted as part of the arsenal for fighting nutritional imbalances.

Table of Contents

1. Introduction

2. Materials and methods

3. Results

3.1 Characteristics of participants

3.2 Anthropometric characteristics at the first investigation

3.3 Evolution of the participants during the weight loss program

3.4 Evolution of participants after finishing the weight-loss program

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

1. Introduction

We enter the 21st century with up to one in four children and adolescents, and more than half of the adults in most developed countries, classified as overweight or obese. International Obesity Task Force estimates that that 1.9 billion people are overweight, and 650 million of these are obese. Of particular concern is the emerging data clearly showing that the epidemic is not confined to developed countries, with many developing countries and those in transition also affected [1].

Obesity and overweight tend to constitute a public health problem and the specific causes and solution for this trend are controversial. In most European countries more than half the population is overweight and 20-30% is obese. Overweight is still an emerging public health problem in Romania and also in developed and developing countries and a challenge to develop modern anthropic food with a balanced nutritional profile, adapted to actual individual metabolic needs and responsive to current changes in eating habits.

WHO reported for Romania 51.0% overweight (49.1% females and 53,1% males) and 19.1% obesity (21.2% females and 16.9 % males). In Iasi county, previous data show that more than 40 % of men and women were overweight and more than 21% were obese, and overweight was related with physical inactivity [2] and digestive illness [3, 4].

Methods for prevention and treatment of obesity include nutritional education, physical activity, diets, drug administration, psychological therapies or bariatric surgery. Diets using conventional or prepackaged foods are frequently used in weight loss programs. Although mainstream drugs for body weight reduction must demonstrate efficacy before receiving a license, food supplements do not need to meet this requirement. Few food supplements have therefore been submitted to clinical trials, and many health-care professionals feel uncertain about their therapeutic value [5].

The purpose of our study was to assess the effectiveness of MR diets in body weight management and the impact in body composition for working age people, when the participants purchased the products and follow the weight loss program outside the clinical trial.

2. Materials and methods

Our research was conducted in the Department of Environmental Health of the Institute of Public Health for weight and body composition monitoring in a framework of a weight loss program.

Participants in this retro-prospective study has been overweight or obese adults who followed personalized low-calorie diets for more than two months. The selected subjects were invited to participate as volunteers in this study and the rules of bioethics and research ethics were followed.

Informed written consent was obtained from all the participants.

Subjects were monitored at least once a month and we recorded the evolution of parameters. In this study we present measurements of the first investigation, at the end of weight loss (final weight) and at the end of monitoring in the maintenance of weight gained.

During the weight loss period we recommended daily calorie intake close to Basic Energy Expenditure (BEE) of the person, which means 1100-1500 calories/day for women and 1300-1700 calories/day for men. BEE (kcal /day) was calculated using the following formula: 370+(21.6 x lean mass in kg) [6].

We monitored the following anthropometric indicators: height (measured in the morning), weight (measured on an electronic scale with a deviation of ±100g, morning fasting and after using the toilet), body mass index (BMI), body perimeters measured using metric ribbon (waist – abdomen, hip – buttocks), percentage body fat. Self-measurement of these indices and their reporting can have sufficient accuracy for trained subjects [7], but we prefer to be performed by the same assessor.

Optimal weight – with minimal health risk – was calculated using the Metropolitan Life Insurance formula that takes account of height in cm (H), age in years (A) and gender: Theoretical optimal weight (kg) = 50 + 0.75 (H-150) + 0.25 (A-20) for men; in women, the result is multiplied by 0.9 [6].

For statistical analysis, data were loaded and processed by use of Microsoft Excel and EPIINFO 7.2 CDC [8]. For descriptive statistics we use mean and standard deviation. We used χ2 test to compare frequencies and t-Student test for calculation of significant difference between the two media. Significance was agreed for p value < 0.05. All analyses were performed separately for males and females.

3. Results

3.1 Characteristics of participants

The study consisted of 79 subjects, 56 women and 23 men. Mean age of patients at study entry was 39.98 ± 13.9 years, ranging from 18 to 69 years. The basic epidemiological characteristics – age, marital status, number of children and level of education – were similar by gender.

3.2 Anthropometric characteristics at the first investigation

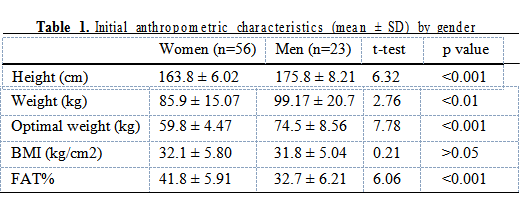

Table 1 shows the initial anthropometric characteristics of the participants. Average height and weight were significantly higher in men than in women (p<0.001). BMI did not differ significantly between sexes (p>0.05), while average FAT% was significantly higher in women compared with men (p<0.001).

3.3 Evolution of the participants during the weight loss program

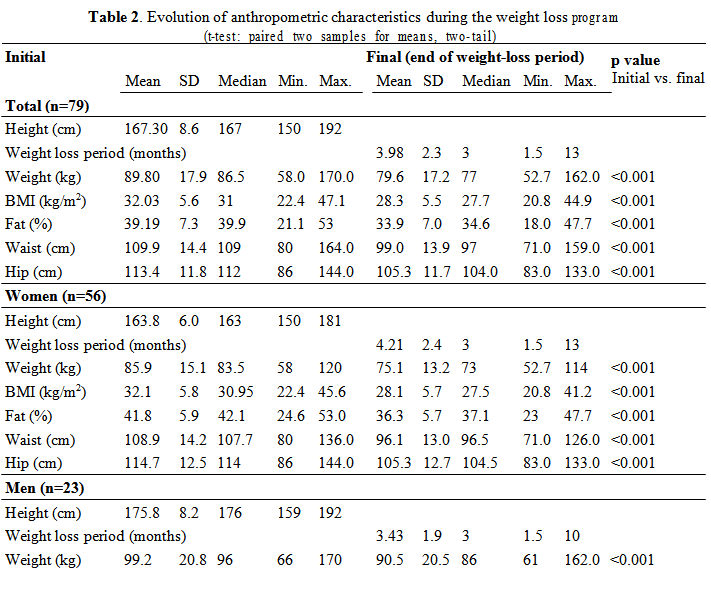

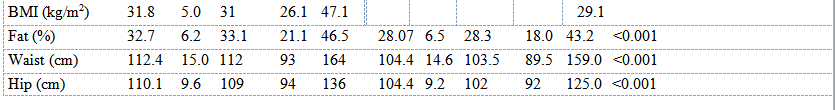

In an averaged time of 3.98±2.29 months, the entire group lost an average of -10.19±6.12 kg, i.e.

11.34% of body weight, -11.47±9.15 cm of waist circumference, -5.29±5.46% of body fat (Table 3).

All the changes were statistically significant (p<0.001). The significance is retained (p<0.05) also for a hypothesized mean difference of body weight of 7% for men and 10% for women.

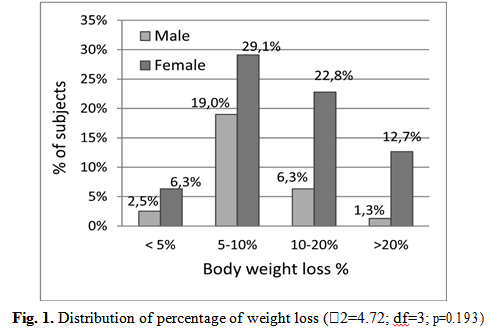

Most of participant lost 5-10% of body weight, but 14% of them lost more than 20% of their initial body weight (Fig. 1).

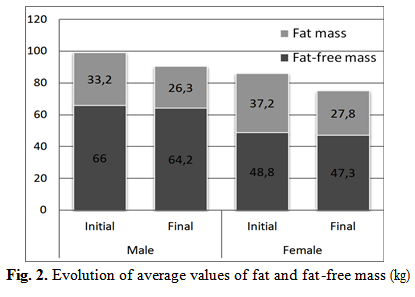

Weight loss was made on account of fat mass, which was significantly reduced by 24% compared to initial (average 20.8% in men and 25.2% in women) and insignificant on account of fat-free mass (3%).

WHR fell significantly from 1.02 to 0.99 in men and from 0.95 to 0.91 in women. Waist circumference as an indicator of central fat distribution recorded significant changes, but the final results were not within the accepted limits. Adherence to the proposed weight loss schedule was higher in women (who have followed the rules for 4.21±2.4 months) than in men (3.43±1.9 months).

The average weight loss was -2.71 kg/month, more in men (average -2.91 kg/month, up to -6.8 kg/month) than in women (average -2.6 kg/month, up to -5.5 kg/month). Most common causes of participants’ left the weight loss program before reaching the target were: financial problems (37%) – monthly cost of imported products was close to minimum wage, lack of motivation for loss weight (33%), monotony (13%), ineffectiveness of program compared to initial expectations (9.2%).

3.4 Evolution of participants after finishing the weight-loss program

Subsequently, in the period of maintenance of weight gained, subjects were followed for an average of 11.28±8.1 months and the entire group of participants reached an average weight gain of +2.86±3.02 kg compared to the minimum weight (31.5% of weight lost) (Fig. 3).

We compared the group that in the maintenance of weight lost replaced one meal a day with MR at least 3 times a week (n=30) with those who rarely or never did it (n=49); these groups were significantly different in the percent of weight regain from totally weight loss (t-test, p<0.001, 12.3% vs. 43.3%).

4. Discussion

Our study demonstrated that the weight loss in a population outside the clinical trial has been comparable or greater than the results published for clinical trials. A randomized controlled study investigated the effect of 12 weeks-long energy-restricted modified diet with or without MRs for weight control on weight loss and body composition in 87 overweight women. Dietary intervention resulted in a significant weight loss in both groups (-5.98±2.82 kg, p<0.001 and -4.84±3.54 kg, p<0.001, respectively).

However, the rate of responder (weight loss >5%) was higher in MR (77%) versus non-MR group (50%) (p=0.010). A significant reduction was observed in waist circumference and body fat mass in both groups [9]. Other study evaluated the impact of a 30-day MR diet (1200 kcal/day, with unlimited fresh vegetables and fruits) in 32 adult primary care patients; mean weight loss was -2.7±2.6 kg [10].

A number of studies have suggested that proteins are the most important mediators of macronutrient sense of satiety, and their increased consumption leads to weight loss with retention of lean mass. An increase in dietary protein content has been proposed to streamline regulation of body weight through effects on satiety, thermogenesis and maintenance or accretion of fat-free mass [11, 12].

In a randomized controlled trial soy and casein meal replacement shakes were compared with energy-restricted diets for obese women and concluded that both study groups with a highly structured behavioral 16 week long program incorporating four MRs and vegetables and fruits lost significant amounts of weight and that differences in weight loss and body composition changes between casein and soy treatments were not significant [13].

Evaluation of the efficacy of two low- calorie diets with partial meal replacement plans (a high-protein plan (HP) and a nutritionally balanced conventional (C) plan in a 12-week randomized double-blind study with 75 participants) showed that the overall mean weight loss was 5 kg in the HP-plan group and 4.9 kg in the C-plan group (p=0.72). Body fat mass decreased 2.5 kg in the HP-plan group (p<0.05) and 2.3 kg in the C- plan group (p<0.05) and the HP-plan was more effective in reducing body fat among subjects with ≥ 70% dietary compliance [14].

Our participants, during 4 months period, lost 8.29±5.26 kg of body fat mass. These better results can be explained by a better adherence to the program and a stronger motivation, possibly because of the price paid for products [15].

5. Conclusions

Excess of body weight is a major public health issue both globally and, in our country, and it still looking for effective weight loss methods applied at individual and population levels. The modern challenge is to develop diets and foods that meet a balanced nutritional profile and are adapted for individual metabolic needs and suitable for current changes in eating habits and lifestyle. Weight loss can be achieved by adopting a personalized diet which considers the fat-free mass, basic energy expenditure and caloric needs of the individual.

The survey showed that replacing two meals a day with MR is an effective way to lose weight. MR energy-restricted diets with slightly increased protein intake resulted in a loss of fat mass with retention of muscle mass. Loss of fat was distributed to the entire body by reducing all perimeters and percentage of body fat. The cost of the products and the monotony of the diet were the main causes of abandon the MR diet. Subsequently, keeping the weight obtained was better in the subjects that replacing one meal a day with MR. Long-term weight loss maintenance is still a challenge and required further research.

MR diets may be an important strategy in combating obesity, because of its efficacy, simplicity and convenience of use [12]. They simplify the composition of energy-restricted diets (defined contents of nutrients and calories), reduce confusion and increase compliance. Such diets are expensive for a large part of the population and become monotonous for long term use. However, most dieticians still maintain that a meal replacement diet is not an appropriate substitute for a healthy lifestyle.

Contributo selezionato da Filodiritto tra quelli pubblicati nei Proceedings “117th Romanian National Congress of Pharmacy - 2018”

Per acquistare i Proceedings clicca qui.

Contribution selected by Filodiritto among those published in the Proceedings “17th Romanian National Congress of Pharmacy - 2018”

To buy the Proceedings click here.